The East Side Free School for Crippled Children

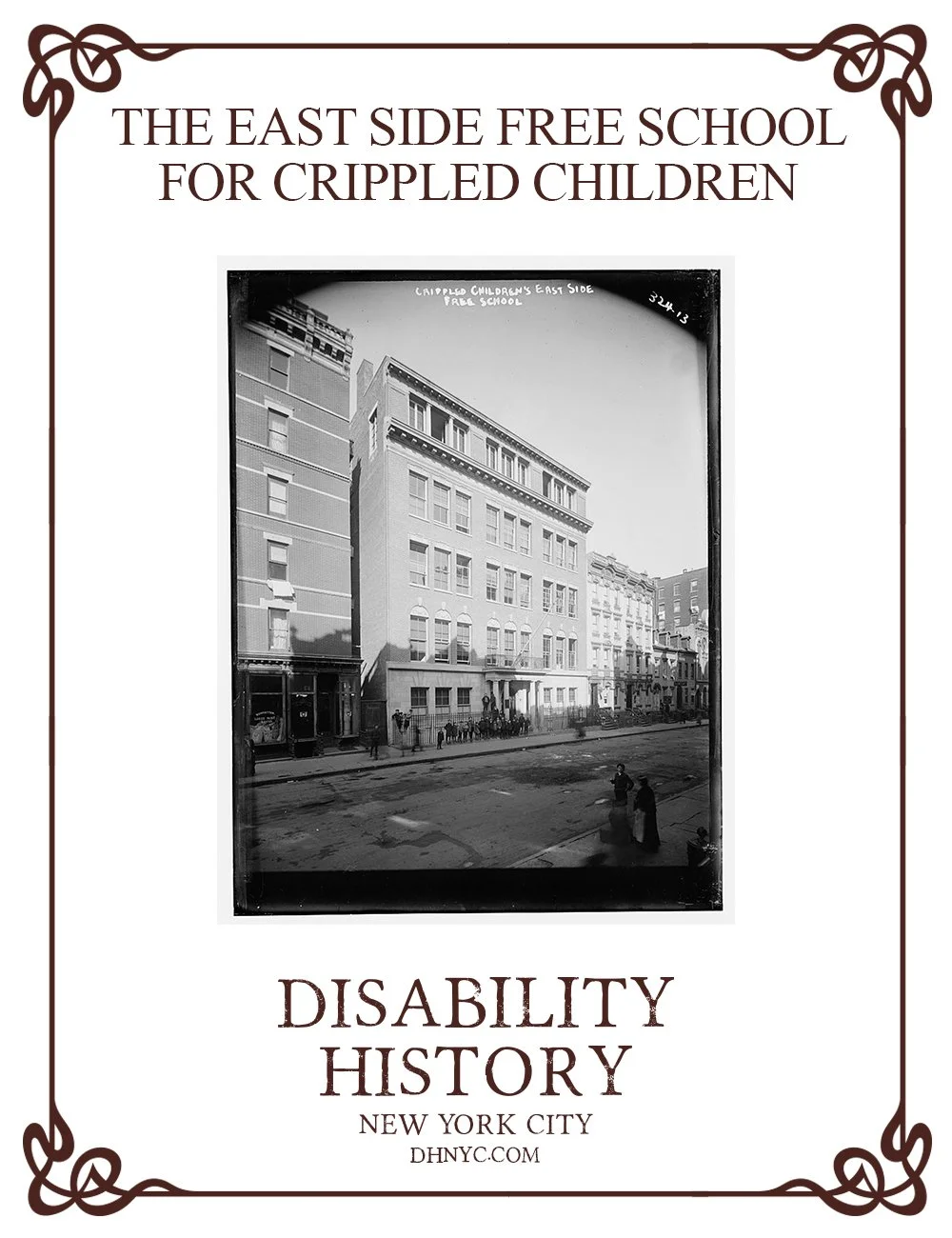

The East Side Free School, 157 Henry Street, circa 1908.

On a quiet block of Henry Street on the Lower East Side, right behind the Forward building, stands a five story apartment house. It boasts a wrought iron fence, a stone base, and some façade decoration. But it’s far easier to miss this building than to notice it. You’d never guess it was once home to the nation’s first school for children with disabilities.

The East Side Free School for Crippled Children was founded in 1900, part of a campaign to provide some sort of education for mobility impaired children, instead of letting them remain hidden away. Over its nearly forty year existence, the Free School grew into a singular, comprehensive provider of education and human services, in a Lower East Side then synonymous with deep poverty and deathly disease.

Like so much early disability work in our City, the campaign to educate disabled children owes its start to the pioneering and long-forgotten activist, May Darrach.

Born in 1869, at the age of thirty, Darrach’s disability put her into the hospital. It was hardly her first time in-patient. But from this particular hospital stay she emerged forever altered, charged with a mission to do something tangible for what she (and everyone else) then referred to as “crippled children.”

157 Henry Street in 2024.

Darrach eventually catalyzed a whole movement, ran her own settlement house, became a physician and practiced medicine. But it all began for her in 1899, when Darrach supposedly wagered Charles Loring Brace, the Secretary of the Children’s Aid Society, that there were hundreds of disabled children hidden away in the tenements, unreached by school, church, or any other outside influence. She knew they were there--she’d shared hospital wards with them. But now Darrach trudged up and down the Lower East Side and documented them. It was the first survey of disability in the general population.

She presented her findings to Children’s Aid, and made her pitch. By the time the year was out, Darrach had begun the nation’s first educational program specifically for children with disabilities--at the Henrietta Industrial School on West 69th Street.

Soon one of Darrach’s allies at Children’s Aid, Mabel Irving Jones, began a disabled kids’ class of her own, and founded what later became known as the Association for the Aid of Crippled Children (or AACC).

In 1900, a group of elite, socially conscious women set up a recreation program in a Lower East Side flat. Kids were brought by horse drawn carriage then carried upstairs, several times a week, to play and hear stories. For many, it was their first opportunity to socialize with other disabled kids. By 1902 the new group had taken a space at 29 Montgomery Street, and renamed itself the East Side Free School for Crippled Children. With classes in reading and handicrafts like sewing, the East Side Free School was soon providing services and transportation to 80 children a day, with no restrictions by race or religion.

In 1906, the Board of Education began the first public school class for disabled children, at PS 67 on West 46th Street. But since the Board’s research showed that more than half the poor children too disabled for regular school lived below 14th Street, it floated the idea of building a school for disabled kids on the Lower East Side.

The standalone public school never happened. Instead, the Board partnered with the East Side Free School to create a hybrid—a settlement house/elementary school/medical clinic—especially for disabled children, in the most notorious slum in the United States.

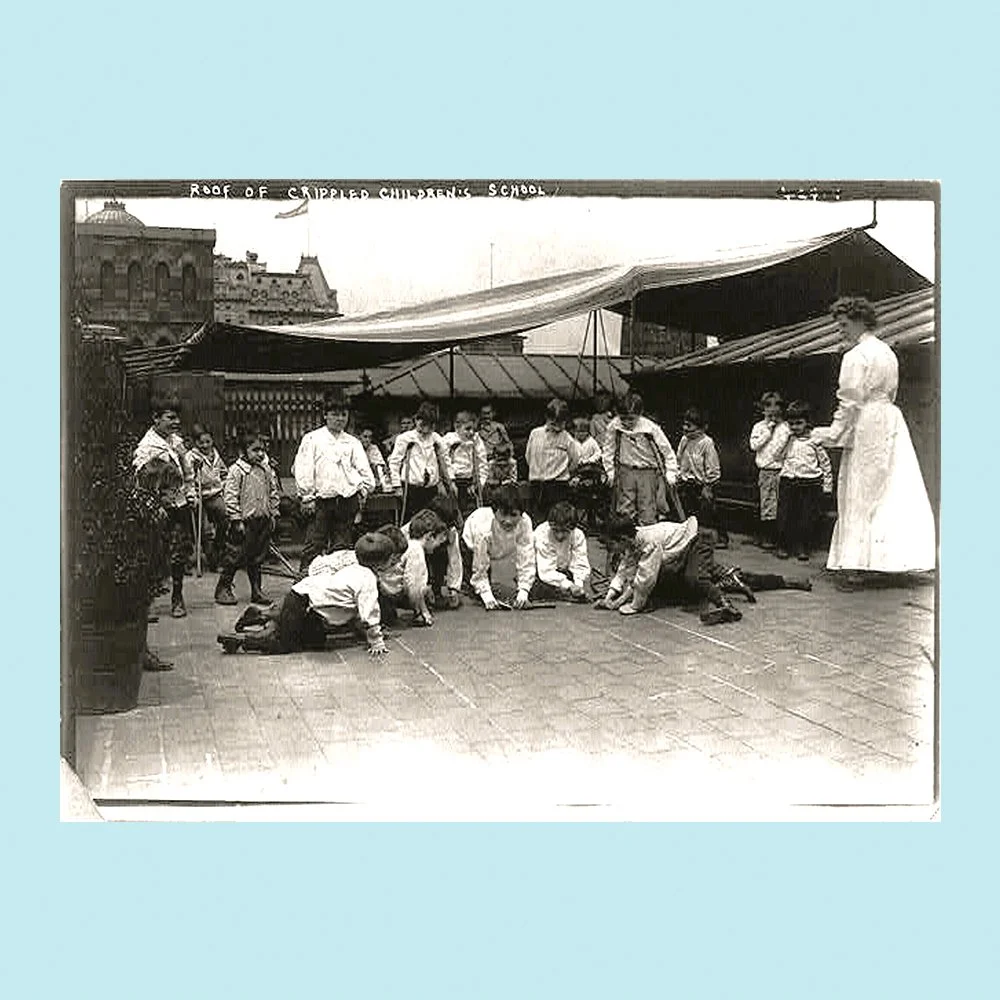

Children on the rooftop playground, circa 1908.

Thanks to a gift from Emanuel Lehman (the uncle of future Governor and Senator Herbert Lehman), in 1908 the East Side Free School moved into its handsome new headquarters at 157 Henry Street (full disclosure: in 1924 my father, the disability pioneer Julius Shaw, was born up the block, at No. 173.) It was in the Lower East Side’s downtown, two blocks from the Henry Street Settlement and around the corner from Rutgers Square, the political and social hub of the then mostly Jewish immigrant community.

The new building was brick with stone trim, five stories tall, with a rooftop playground and even an elevator--a long way from the walk-up tenement where the school had begun.

The building’s external symmetry concealed its internal complexity. It housed four essentially independent units.

First there was a public school, funded, staffed and equipped by the Board of Ed, with space for up to 190 students.

Second was a privately-funded social work component, providing transportation, afterschool and Saturday playtimes, meals (including dinner)--and physical hygiene, or “bathing,” as they called it, twice a week. That was important in a neighborhood where adequate bathrooms were a novelty. More than 9700 baths would be administered in 1912 alone.

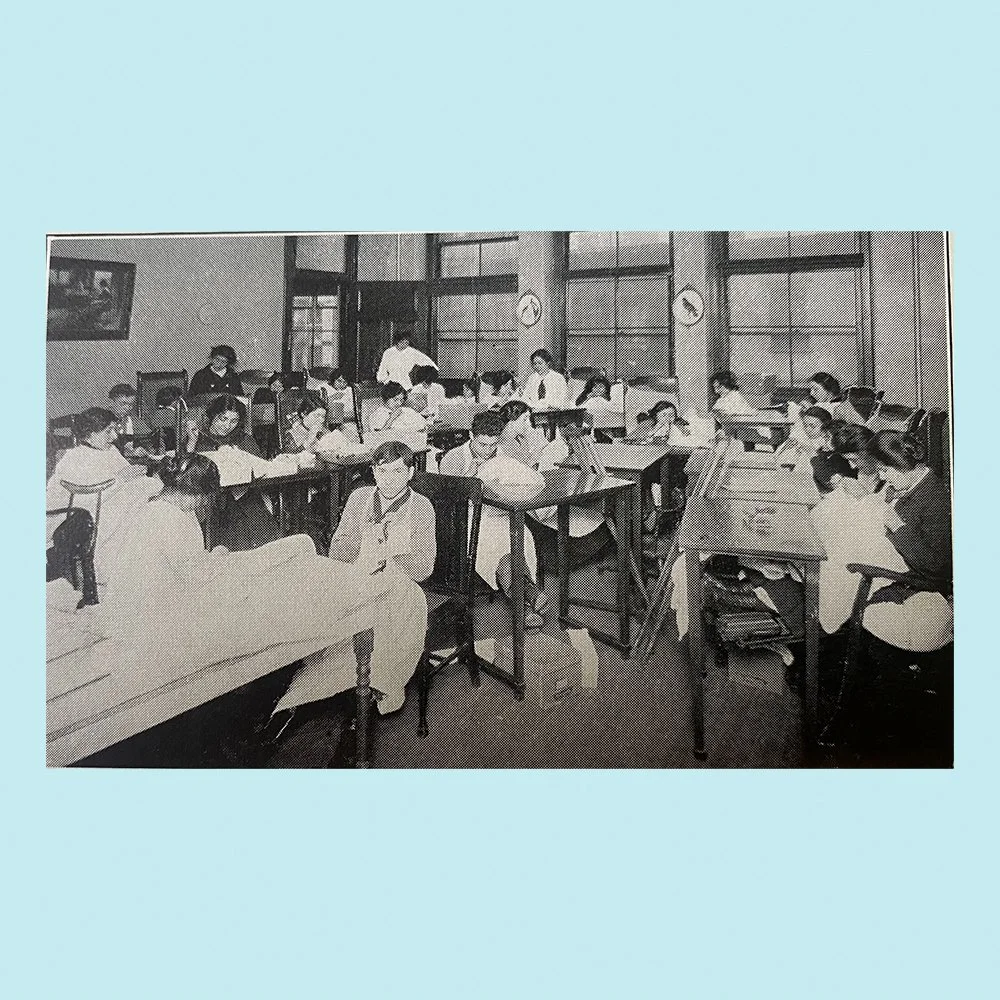

Third, older kids were trained in marketable skills, and there was a workroom where up to 26 people earned regular wages, consistent with the Free School’s mission: “to improve the children’s physical condition, to train them to become self-supporting, and to provide them with work.”

Finally, there was a privately-funded health clinic with physicians and nurses on staff, offering medical care and even some surgery, on an outpatient basis.

It was a complete facility for physical, intellectual and social development. For some of the most vulnerable kids, in one of the poorest places in the United States.

The workroom for older children and adults, circa 1912.

By any measure, May Darrach’s education campaign had really taken off. As the New York Times exulted in 1908, the City led the nation when it came to schooling for children with disabilities.

By 1913, the East Side Free School was flourishing. It opened a summer camp in Oakhurst, New Jersey, which is still in operation under the name Rising Treetops.

But the isolation of disabled children that was documented in Darrach’s first-ever survey--that went on unabated. In 1913 the AACC conducted another survey, this time on a single block of Cherry Street between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges (then known as Cherry Hill). Home to more than 1100 families, the survey found large numbers of disabled children. Three quarters of them had no medical care.

Given so great a need, the children with disabilities movement continued to grow. Organizations multiplied: the William H. David School, the Brearley League, the Day Home and School, the Miss Spence School, the Free Industrial School, the New York Home for Destitute Crippled Children. Nearly a thousand disabled children attended a performance of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Wicked World” at the Lyceum Theater, featuring a cast drawn almost entirely from students at the East Side Free School. In 1911 the kids at May Darrach’s own settlement home put on an operetta, “The Stolen Princess.”

In 1922 the Visiting Guild for Crippled Children transformed into Blythdale Children’s Hospital. The AACC held a blockbuster fundraising street fair on Park Avenue from 46th to 50th Street, headlined by Fanny Brice and Eddie Cantor.

But by 1938, however, the Free School had run out of time.

It had been a human services pioneer, penetrating into Dickensian misery. It had remained in operation long after most of its contemporaries had closed. But the world had changed and enrollment was declining, and it’s not hard to see why.

Medical infrastructure and access expanded enormously after the great Polio Epidemic of 1916 and the 1917-18 Flu Pandemic. So there was less need for the Free School’s clinic. Its educational function was being duplicated at public schools across the City. And between the building boom of the Twenties, the beginnings of Urban Renewal, and amendments to the Multiple Dwelling Law, the Lower East Side’s bathroom shortage was diminishing, so the personal hygiene function was losing its importance.

The era of the neighborhood settlement house was done.

On June 22, 1938, the Free School shut down. A few years later the building reopened as an apartment house. It continues in that role today.

I recently asked a few of the tenants whether they knew that the building had once housed a school for disabled children. None of them had any idea.

This building ought to have an historical plaque or marker, something to remind the world of what used to be, for kids with disabilities. Today the neighborhood is largely wealthy, nearly unrecognizable in many ways. But poor children with disabilities are still with us. They deserve a public place, and a point of beginning.

Note: A version of this entry appeared in Able News, https://ablenews.com/