Federation of the Handicapped

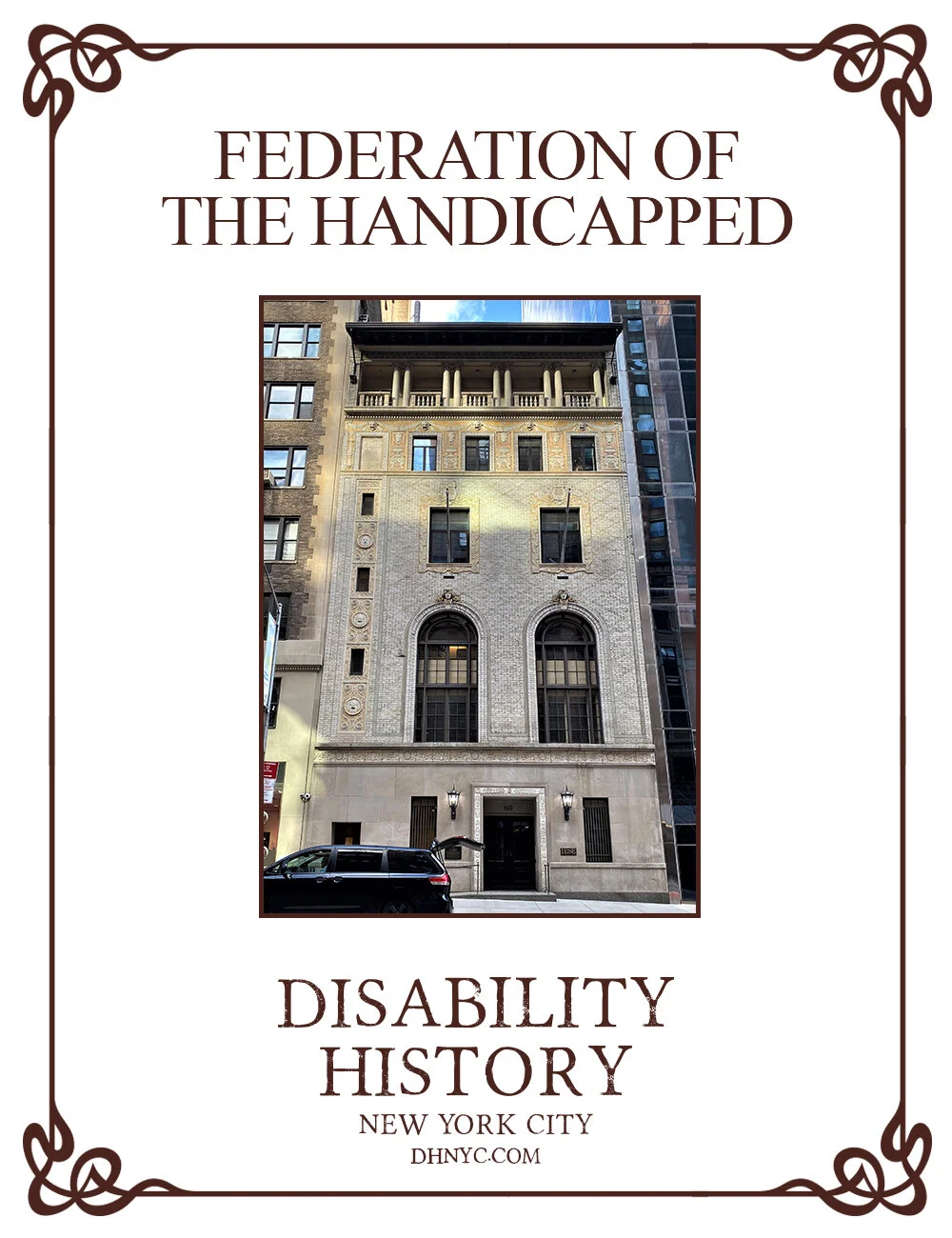

In this image: Photo of 163 West 57th Street, also known as “Cami Hall,” which was owned and occupied by Federation during the 1940s.

Federation for the Crippled and Disabled was the first entrepreneurial self help effort by and for people with disabilities. It began in the Spring of 1935, within weeks of the formation of the League of the Physically Handicapped, and emerged as a private not-for-profit effort whose mission combined self-help, sociability and fraternal support with job training and employment for people with disabilities. Federation has not generally been considered in the context of disability activism, but that omission has been in error.

Federation found its beginnings in a chance meeting of three unemployed disabled men on the sidewalks of Times Square. They were drawn together by a police officer’s encounter with one of them, a double amputee selling pencils and similar small goods. Concerned that an arrest might be in the offing, two single amputees came to back up the legless man. They fell into conversation after the seller established to the officer’s satisfaction that he was a licensed dealer, not a vagrant. Over coffee, the three men—Michael Bertero, Ralph L. Rice and Robert Boster—sat down to compare their stories. Drawn together by their common impairments and shared state of unemployment, all three were caught in a vicious circle: the labor surplus caused by the Great Depression presented a nearly insurmountable barrier, yet their disabilities left them with few options. Each of them had independently recognized that an organization of people with disabilities might provide a path to a better future, and they pledged to found an organization devoted to improving the situation of adults with disabilities.

The trio’s concept was a combination of social club and mutual aid society, intended to improve the circumstances of members through job training and assistance in job placement. In a grim illustration of the dire circumstances faced by Federation’s founders and those like them, its certificate of incorporation specifically provided that the new organization’s purposes included preventing vagrancy and covering funeral costs for families too poor to do so on their own.

Federation was soon providing on-the-job training in watch-making, stenography, printing and other suitable occupations. It also succeeded in placing unskilled disabled workers in hospitals and hotels. It was at this stage in Federation’s development, with about ninety members, that it first incorporated, in 1937. Membership soon grew to over eleven hundred, a remarkable accomplishment that required moving to larger quarters. More than a quarter of the members came seeking job training and placement assistance, and Federation developed considerable expertise in screening members for their aptitudes and abilities, and in developing appropriate programs and training.

Needing a larger space, in 1942 Federation purchased its first headquarters. Showing questionable judgment, instead of selecting a modest second- or third-tier property, Federation made a conspicuous, and conspicuously lavish, choice--a palatial six story structure directly across from Carnegie Hall, which remains well known today as Cami Hall. The founders saw this acquisition as a sign that their organization had arrived. As Bertero wrote in the Long Island Star Journal, “the dream conceived seven years ago [became] a realization . . . when the official opening of our new home at 163 West 57th Street took place . . .”

This self-congratulation proved very much mistaken.

Bertero, Boster and Rice had set themselves up as officers, Board members, and staff, both raising the funds and deciding how they should be spent without any of the internal checks and oversight typical for not-for-profit organizations. Between this at best dubious organization and the group’s almost nonexistent record-keeping, the New York State Attorney General began proceedings to revoke Federation’s corporate charter. This potentially fatal situation led to a dire cash shortage, as donations plummeted. Programs abruptly closed and 125 workers were let go. Bertero, Boster and Rice were ousted. Losses necessitated the sale of the 57th Street location and a move to less costly quarters downtown. The organization also changed its name to Federation for the Handicapped.

For many, many years Federation provided important social outlets for its members and trainees, with both formal and informal weekend, monthly and holiday events--dances, dinners, card parties, professional entertainers, guest speakers and the like. But over time, the struggle to generate income diluted the organization’s self help mission. Federation increasingly turned to a sheltered workshop model, and by the end of the 1960s, Federation stopped its efforts to provide sociability and job training, and halted its innovative, disability-friendly vacation and travel programs—or, at least, it stopped publicizing them.

With rote assembly-line work now all but synonymous with the organization, Federation drew the stigma and disdain that the disability community has long felt towards sheltered workshop employment. It played no part as the modern New York City Disability Rights Movement got underway in the 1960s, and those activists went about their mission with little or no idea that Federation’s origins lay in the earlier iteration of that same cause.

More recently, the dilution of Federation’s original purpose reached its conclusion: in 2015 Federation sold its longtime headquarters on West 14th Street and moved to midtown offices where, having merged with a number of other organizations and under a new corporate moniker, Fedcap, it has become just another star in the nonprofit firmament, no doubt serving a useful purpose but with no connection to the purpose that brought it into being.

by Warren Shaw