Marvelous Marvin Wasserman

"A kind and principled leader."

Sharon Shapiro-Lacks, Board member and former Executive Director of the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled

(or BCID).

"Marvin has tirelessly devoted his effort, strength and whole self. Without him, the disability movement would look very different today."

Heidi Hirschfeld, President, BCID Board of Directors.

"Marvin shared his political savvy and promoted cooperation between groups."

Jean Ryan, President, Disabled In Action.

"Pioneering by organizing politically, Marvin saw a future in which the needs, rights and voting power of the community are acknowledged by those who run for office."

Jim Weissman, Legendary Movement Litigator.

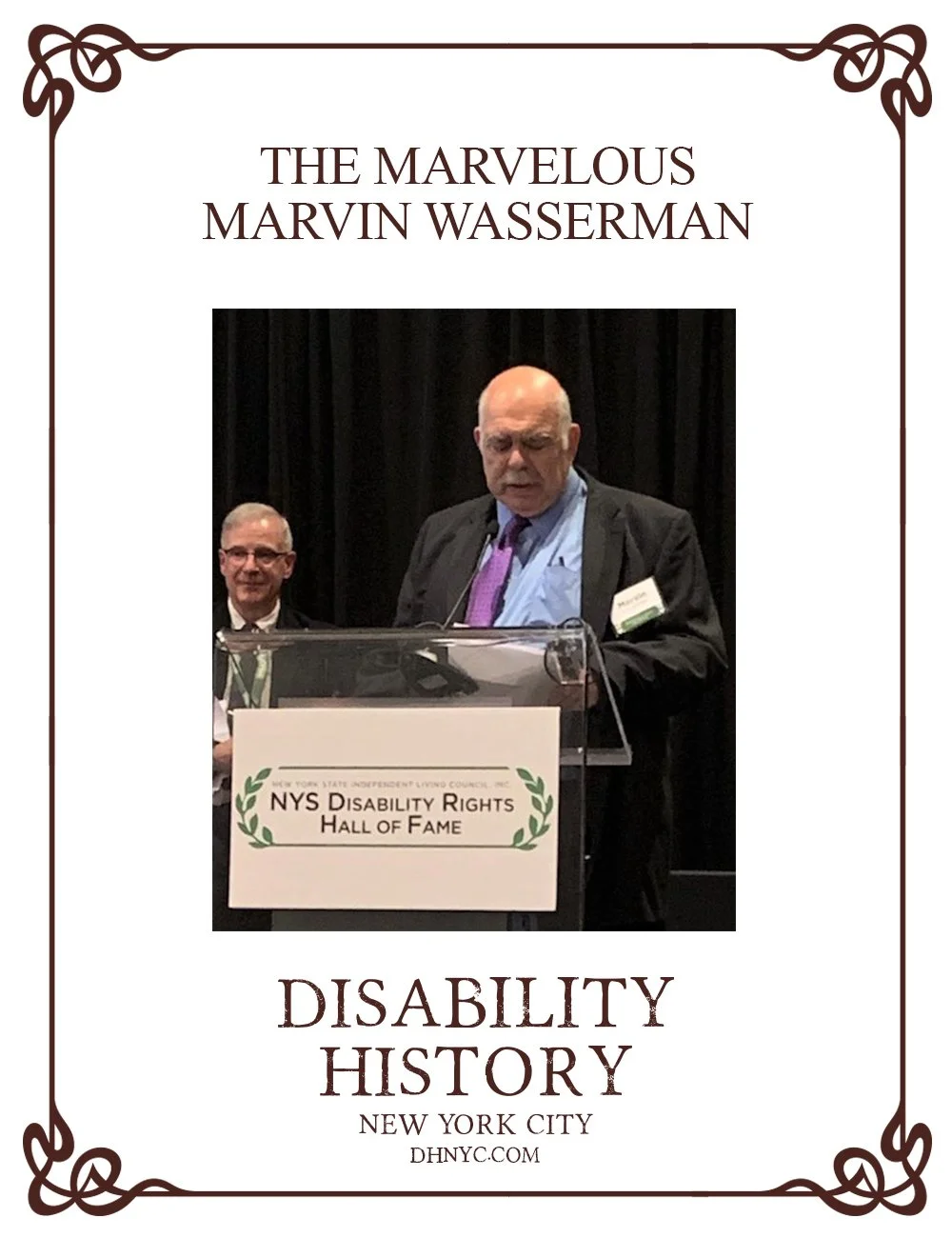

In this image: Marvin Wasserman accepting induction to the NYS Disability Rights Hall of Fame on behalf of the late Sandra Schnur. On the left is Brad Williams, E.D. of New York State Independent Living Council (or NYSILC), which oversees the Hall of Fame.

As a jazz fan, I think of Marvin Wasserman as the Freddie Hubbard of the New York City Disability Rights Movement. He knows his stuff through and through. He’s worked with more people, accomplished more and done more mentoring than just about anyone. But I don’t think he ever became a household name. It’s even possible that you, Dear Reader, may not be familiar with him--the man sometimes known as “Marvelous Marvin,” the man who helped create the 504 Democratic Club, co-founded the Taxis for All Campaign, and led a revival of the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled.

Marvin had a rocky start. Born in Brooklyn in 1945, Marvin’s parents separated when he was two years old. He wound up in foster care, living over the next four years in a succession of farms in New Jersey, before reconnecting with his mother.

At the age of eight, living in Brighton Beach, Marvin was heading to meet his mother on a dark rainy night when he was somehow hit by a trolley car. He lost consciousness from the impact, the first of several head injuries that led to a case of epilepsy which went undiagnosed for many years.

By the time he finished high school, in 1962, Marvin had already found the major passions of his career—party politics and political activism. He joined the Young Reform Democrats of Brooklyn and co-founded a student chapter of the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, or SANE. This work led to involvement with reform candidates and organizations in Brooklyn and the Lower East Side. Marvin found himself sharing a picket line with Mickie Schwerner, one of the three activists murdered during Mississippi Summer (the subject of the film “Mississippi Burning”). He attended the pivotal March on Washington, on August 28, 1963, where Martin Luther King delivered his famous “I Have A Dream” speech.

In 1968, college student Marvin helped organize a chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society, or SDS, and campaigned for Eugene McCarthy, who was challenging Lyndon Johnson for the Democratic Presidential nomination.

Armed with a BA in Sociology, Marvin made a beeline for party politics, running for Democratic District Leader and New York State Democratic Committee. Neither campaign was successful, but he wound up President of the Queens County New Democratic Coalition, which worked in opposition to the infamous Borough President Donald Manes.

Having by now received his epilepsy diagnosis, it was perhaps inevitable that Marvin eventually found his way into disability activism. Contacts with movement stalwarts like Kurt Schamburg, Elaine Pomerantz and Marilyn Saviola followed.

Through his Democratic party work, Marvin had become aware of efforts to found issue- and demographically-focused political clubs, such as the Rachel Carson Club, which focused on environmental issues, and a lesbian and gay club. These examples planted the seed for what would become his most central accomplishment—a political club targeted to New Yorkers with disabilities.

Getting this idea off the ground took several years, and in the process Marvin came into contact with another movement figure, Sandra Schnur (best remembered as a founder of Concepts of Independence (see Concepts of Independence )). Sandra and Marvin got married in 1983, and they remained inseparable, until Sandra passed away in 1994.

In this image: Marvin Wasserman 2012

The new organization, the 504 Democratic Club, eventually developed a well-defined practice of endorsing electoral candidates, educating them on disability issues, and lobbying officeholders, just as Marvin had envisioned. 504 is practically unique in the United States (see The 504 Democratic Club ), and it has proven critically important in boosting community visibility and access to public officials.

Marvin’s success with 504 led to another major project—the Taxis For All Campaign (see Taxis for All Campaign ). An outgrowth of the long fight for accessible busses and 100 accessible subway stations, Taxis For All brought together Terry Moakley, Frieda Zames, Alexander Wood, Edith Prentiss, and more. The campaign achieved lasting and palpable impact: today, a third of the City’s cabs are accessible to wheelchair users; e-hail cab service has been established; and companies like Uber and Lyft have agreed to important accessibility accommodations.

In 2008 Marvin was elected Executive Director of the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled, or BCID. BCID had been on probation with its supervisory agency, New York State’s Vocational and Educational Services for Individuals with Disabilities (or VESID). But over the course of Marvin’s tenure as E.D., BCID recovered and expanded (see Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled ). And it took on high-profile projects, like BCID v. Bloomberg, a federal class action that challenged the City’s failure to provide accessible emergency facilities.

In an era of climate change, Hurricane Irene and Superstorm Sandy, this was a more timely issue than ever before, and the litigation resulted in a settlement which, in the words of BCID’s counsel, meant “sweeping improvements to the City’s emergency preparedness programs and services, including all major emergency planning areas,” impacting “the lives and safety of nearly 900,000 New Yorkers with disabilities.”

Serving as E.D. of BCID was “like being a kid in a candy store,” according to Marvin. But it was an all-consuming and exhausting position, and after four years he stepped down. Remarried by then to Rita Seiden, a psychotherapist and social worker, Marvin retired and moved to California.

A large man with a substantial mustache, Marvin moves and speaks with deliberation, but his personal warmth and political brilliance are impossible to miss. Now 79, Marvin remains on BCID’s Board of Directors. As a fellow Board member, I can attest to Marvin’s continuing grasp of the New York City Disability Rights Movement, even from three thousand miles away.

“Marvelous Marvin” has long been an active and generous mentor, collaborator and friend. Christina Curry, Commissioner of the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, spoke for many when she told me that “Marvin Wasserman is a strong advocate, he will let you know what is on his mind without hesitation, he is not afraid of change, confrontation or even admitting when he does not know something. It was my honor to work alongside him, and I am proud to call Marvin a friend.”

DHNYC thanks Christina Curry, Heidi Hirschfeld, Joe Rappaport, Jean Ryan, Michael Schweinsburg, Sharon Shapiro-Lacks and Jim Weissman for their assistance in the preparation of this entry.

by Warren Shaw

Note: A version of this entry appeared in Able News, https://ablenews.com/